The

Sandhill Crane

(Grus Canadensis)

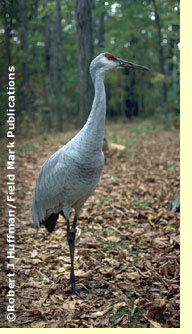

The Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis) is one of only 15 species of cranes in the world and is one of just two crane species native to North America. While the Whooping Crane, our other native crane, is highly endangered and restricted to only a few areas of the West, the Sandhill is more widespread and in most areas is more abundant. Once nearly eliminated from Michigan, Sandhill Cranes have made a comeback and now are becoming one of the state's most popular watchable wildlife species.

Cranes are tall, stately birds with a heavy body, long neck and long legs. Standing four to five feet high and possessing a wing span of six to seven feet, Sandhill Cranes are Michigan's largest bird. Long, skinny legs and neck give a false impression of size; the males weigh an average of about 12 pounds and the females around 9-1/2 pounds. Except for this size difference, both sexes look alike.

After molting their feathers in late summer, Sandhills are gray except for white

cheeks and a bare reddish forehead. Bustle-like feathers further add to a distinctive

appearance. The intensity of red in the bald forehead varies depending on behavioral

stimulation which controls skin capillaries by restricting or relaxing blood flow. A

brighter red forehead is associated with stressful stimuli; on the other hand, a less

conspicuous forehead signals submission. Sandhills frequently preen with vegetation and

mud stained with iron oxide. Consequently, during most of the year they appear reddish

brown rather than gray. Only the hard to reach areas of the upper neck, underwings and

head will lack the rusty coloration once the process is completed. This unusual behavior

aids to camouflage the nesting birds. Immature Sandhills appear similar to adults except

that they are brown in color and the forehead remains feathered until early winter.

After molting their feathers in late summer, Sandhills are gray except for white

cheeks and a bare reddish forehead. Bustle-like feathers further add to a distinctive

appearance. The intensity of red in the bald forehead varies depending on behavioral

stimulation which controls skin capillaries by restricting or relaxing blood flow. A

brighter red forehead is associated with stressful stimuli; on the other hand, a less

conspicuous forehead signals submission. Sandhills frequently preen with vegetation and

mud stained with iron oxide. Consequently, during most of the year they appear reddish

brown rather than gray. Only the hard to reach areas of the upper neck, underwings and

head will lack the rusty coloration once the process is completed. This unusual behavior

aids to camouflage the nesting birds. Immature Sandhills appear similar to adults except

that they are brown in color and the forehead remains feathered until early winter.

The Sandhill Crane is often confused with the Great Blue Heron. Both are large wading birds with pointed bills, long necks and legs, but they do have some major differences. Herons fly with the head and neck tucked back to their shoulders in an "S" while cranes fly with their necks outstretched. The rapid upstroke of the wings is a good field mark for cranes in contrast to the slow steady flap of Great Blue Herons. Cranes nest separately on the ground, while herons nest in large colonies in trees called rookeries. Finally, cranes have a loud trumpet-like call, while the Great Blue Heron utters low hoarse croaks.

Voice

Sandhill Cranes have a variety of vocalizations, the

most common of which is generally described as a repeated series of trumpeting “garoo-a-a-a”

calls that can be heard for over a mile. One of the reasons for this remarkably loud and

penetrating call is an unusual windpipe. In most birds the trachea passes directly from

the throat to the lungs, but in Sandhills it is elongated by forming a single loop which

fills a cavity in the sternum. It is not surprising that the louder and more harmonic

Whooping Crane has a longer trachea with a double loop.

Perhaps the most remarkable call of cranes is the unison call. It is typically uttered when they begin to pair. Unlike the single-noted calls, the unison call is a complex and extended series of calls uttered by a pair of the birds standing in a specific posture and spatial relationship to each other. They call in synchrony, but the calls and postures of the sexes differ. The female begins calling and usually utters two notes for every one given by the male. With each call the female elevates her bill about 45 degrees and then returns it to horizontal between calls, whereas the male raises his bill nearly to vertical while calling.

Subspecies

Of the six recognized subspecies of Sandhill Crane,

it is the Greater Sandhill Crane that we find in Michigan. The Greater sub species can

also be found in the Far West. In between we have the Lesser and Canadian subspecies that

winter in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, California and Mexico and migrate to their nesting

grounds in central and western Canada, Alaska and even Siberia. Lessers nest in the

arctic, while the Canadian subspecies breeds in the aspen parklands of central Canada.

These two subspecies comprise most of the Sandhill Cranes in North America.

The spectacular early spring migration of over one-half million Sandhill Cranes through the North Platte River area of central Nebraska is comprised primarily of Lessers. The same birds provide limited hunting opportunities for sportsmen in many western states and Canadian provinces as they return south each fall. The other three subspecies are all southern and non-migratory. The Florida subspecies occurs across southern Georgia and northern and central Florida. While the Florida subspecies occurs in good numbers, the other southern subspecies, the Mississippi and the Cuban, are both highly endangered. The Mississippi subspecies is restricted to only one county in that state, and the Cuban subspecies is now mostly restricted to the Isle of Pines. The future does not look bright for these two subspecies. However, the Greater Sandhill Crane population in the Great Lakes states is expanding in both numbers and range.

Food

Habits

Sandhill Cranes are opportunistic omnivores. Because

they frequent marshes for protection, many people mistakenly believe that Sandhills feed

on fish much like the herons. Although they will occasionally eat fish, their diet

normally consists of a wide variety of both plants and animals. They readily take

advantage of available food supplies. Early in spring, when food is scarce, they may

scavenge waste grain in cattle pastures. Cranes do a great deal of digging with their

bills, often penetrating several inches below the surface in search of a morsel. Animals

such as snails, crayfish, worms, mice, birds, frogs, snakes, and many kinds of insects are

consumed. They also devour acorns, roots, various seeds and fruits, and browse vegetation.

They are especially fond of harvested grain such as corn, wheat, and barley. Unfortunately

for farmers, cranes often pull newly planted corn and each year some localized severe crop

damage is reported. However, cranes also benefit farming by consuming weed seeds, harmful

insects, and waste grain which, if left in a field, would compete with the next year's

crop.

Spring

Arrival

The annual return of Sandhill Cranes is a sure sign

of spring. The urge to migrate moves them from their warm winter quarters to the cold,

snowy landscape of Michigan. Arriving in mid February in southern Michigan and nearly a

month later to northern Michigan, they are one of the earliest migratory birds to return.

Unlike Sandhills in many other areas, Michigan Sandhills seldom gather in large flocks

during spring migration, but rather disperse to their nesting territories.

Sandhill Cranes mate for life and pairs return to the same nesting locations year after year. When a pair flies north they usually are accompanied by the one or two offspring from the previous year which the parents have so carefully protected. These youngsters are in for a rude awakening, however, since shortly after arrival on the nesting ground, the adults drive the young out of the area. Sandhills are very territorial, not allowing other Sandhills near their nesting area, not even their previous year's offspring. For the next several years these youngsters will roam rather unpredictably in loosely-knit flocks. Eventually they find partners and establish territories of their own. Territories usually cover between 40 and 200 acres, but some 10 acres or less in size have been noted.

Courtship Display

Cranes are famous for their dance. The

dancing display of cranes is often associated with courtship. Young unpaired birds will

also dance suggesting that it serves other functions such as thwarting aggression,

facilitating pair formation, and sexual synchronization. The dance consists of a series of

bowing, jumping and stick-tossing movements. When it occurs in a flock, it often begins

slowly with one bird, then increasing in tempo, the excitement of the dance soon spreads

to others until many are dancing at the same time. It certainly is one of the most

interesting of animal behaviors to observe.

Nesting

![]() Traditionally, cranes select remote inaccessible wetlands

for nesting. Sandhills are using smaller wetlands, frequently within sight of human

activities, and with a greater variety of vegetative cover types. In the past they would

fly away at the first sign of human intruders. Now, they are more apt to stay and defend

their nest.

Traditionally, cranes select remote inaccessible wetlands

for nesting. Sandhills are using smaller wetlands, frequently within sight of human

activities, and with a greater variety of vegetative cover types. In the past they would

fly away at the first sign of human intruders. Now, they are more apt to stay and defend

their nest.

Nesting begins early in April. Large nests are constructed of vegetation pulled from the nearby area to form a mound often surrounded by a moat, but some nests have been located on dry land. The average nest is two to three feet in diameter and rises three to five inches above the water. Sandhills typically lay two oval-shaped eggs about twice the size of a chicken's egg. They are either greenish or brownish with small dark brown spots. Eggs are laid between 24 and 48 hours apart. Both parents share incubation duties and raise the young. Although the female does most of the incubation while the male protects the nest from intruders, they do periodically exchange duties. After about 30 days, the eggs hatch. Since incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid, hatching does not occur at the same time. The older chick often attacks the younger chick, resulting in only one offspring being raised by a pair. It is common for young Sandhills to be away from the nest within 24 hours of hatching, but they may return at night, allowing the female to brood them. The young grow rapidly, feeding on a variety of plant and animal life found both in wetlands and in surrounding uplands. Within ten weeks they are ready to take their first flight.

Fall Staging

Toward the end of summer, Sandhill Cranes

begin a remarkable change in behavior. Since spring, they have been very territorial,

driving away any would-be intruders. Beginning in August, Sandhill pairs become less

antagonistic to other Sandhills and slowly become more social. They begin by feeding

together in the same field, then roosting in small flocks at night, and finally gathering

in large flocks at staging areas. This loss of aggressive behavior enables pairs to

benefit from the advantages of migrating and wintering in flocks.

At fall staging areas Sandhills provide excellent bird-watching opportunities. Staging areas are wetlands usually within a day's flight of nesting marshes that offer food, social interactions and protection prior to migration. Cranes spend the night roosting in shallow open water areas. Early in the morning, they fly out to feed and loaf in agricultural fields, returning late in the afternoon to roost. The sight of several hundred cranes flying low overhead, uttering their prehistoric calls as they wing their way back to roost, is one of the most aesthetic in all nature. Hundreds of crane watchers also “flock” to staging areas each fall to enjoy the spectacular gathering of cranes.

Sandhill Cranes are secretive during the breeding season. The best viewing is in autumn at the larger and more accessible staging areas. The best time of day to see cranes is early morning and late afternoon. Since weather can be changeable in the fall, it is always advisable to bring foul weather clothing. Of course, binoculars and cameras are always a good idea.

The largest concentration of Sandhill Cranes in the Midwest occurs at the Jasper-Pulaski State Fish and Game Area in Indiana. Located just west of Radioville on US 421, it is about 40 miles south of Michigan City. From October through November Sandhills from Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario stop at Jasper-Pulaski during migration. More than 30,000 Sandhills have gathered there in early to mid November during the peak of migration.

Crane enthusiasts might also want to visit the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo, Wisconsin. During guided tours, visitors will see most of the species of cranes found in the world, and learn of foundation-sponsored projects carried out around the world. Further information may be obtained by writing: International Crane Foundation, E-11376 Shady Lane Road, Baraboo, Wisconsin 53913.